Ornamental artillery plant, Pilea microphylla, aka gunpowder or pistol plant, military fern, or rockweed, is an herbaceous perennial.

It is one of about 600 types of non-stinging Pilea species in the Urticaceae, or nettle family.

This tropical species thrives outdoors year-round in Zones 11 to 12 as a short-lived evergreen perennial. It is also grown as an outdoor annual or indoor houseplant in all zones.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

In this article, we’ll discuss all you need to know to grow and care for your own artillery plant indoors.

It has a creeping growth habit and may reach mature dimensions of six to 18 inches high and 12 to 24 inches wide.

The artillery species has plump leaves like a succulent. They are either green or variegated pink and white, one-eighth to one-half inch long, and “obovate,” or rounded and narrower at the base. The leaves are arranged in opposing pairs, like a fern frond.

In nature, the species produces tiny pinkish flowers followed by brown fruits. And while flowering is unlikely to occur indoors, it’s fun to know about it because the names “artillery,” “gunpowder,” “military,” and “pistol” come from an unusual characteristic.

There are both male and female flowers, and the males literally propel pollen into the air, as in an aerial attack.

Historically speaking, the artillery species has undergone numerous botanical reclassifications by Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus and later botanists, including Parietaria microphylla (1759), Pilea muscosa (1821), P. microphylla (1851), and P. trianthemoides var. microphylla (1869).

These synonyms and “basionyms,” or name equivalents and their predecessors, still pop up in plant searches, so it’s good to be familiar with them.

The artillery species is native to the Caribbean, Mexico, Central and South America, and the southeastern United States.

In its native habitat, it is a somewhat weedy, spreading ground cover that commonly sprouts between rocks and in lawns, in margins between land and water, and in masonry crevices.

The species has been introduced around the world, and is classified as invasive or at high risk for becoming invasive in many places because it readily naturalizes via stolons, or runner roots, as well as self-sown seed.

Today’s cultivated varieties are robust versions of the hardscrabble wild species. And while indoor cultivation does not pose a threat to the landscape, we do not recommend letting P. microphylla spend the summer outdoors in temperate zones as we do with many houseplants, in order to avoid inadvertently introducing it to the landscape.

This tropical species thrives best with a daytime temperature range of 65 to 85°F and 1000 to 2000 foot-candles of daylight, which is another way of saying bright indirect light.

Lower light is well-tolerated but usually causes shading to dark green, so don’t waste money on a variegated variety if you choose a dim location for your plant.

And growth may be more horizontal than upright. A little pruning of leggy stems contributes to a more compact form.

If you have a very dim setting, such as a windowless office, that you wish to add a plant to, you’ll need a grow light.

To grow your own P. microphylla, you’ll need to start from seed, take a stem cutting from an existing plant, divide an existing plant, or purchase a nursery start.

Outdoors, this is a vigorous self-sower that disperses tiny seeds with gusto, contributing to its invasive tendencies.

However, starting from seed may pose a challenge, as most retailers sell live plants and seeds can be hard to come by.

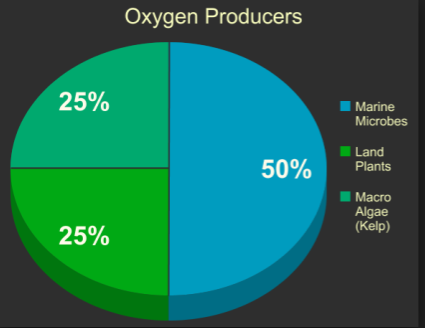

The artillery plant (Pilea microphylla) is an intriguing and visually appealing houseplant that not only enhances indoor spaces with its aesthetic charm but also contributes to improving air quality One of the key benefits of having indoor plants is their ability to produce oxygen through photosynthesis In this comprehensive guide, we will dive into how much oxygen the artillery plant produces and its overall impact on indoor air quality.

Understanding Photosynthesis and Oxygen Production

Photosynthesis is the process through which plants like the artillery plant use sunlight, carbon dioxide from the air, and water to produce food in the form of sugars and oxygen as a byproduct. The chemical equation for photosynthesis is:

6CO2 + 6H2O + Light –> C6H12O6 + 6O2

This shows that for every molecule of sugar (C6H12O6) produced, six molecules of carbon dioxide (CO2) are taken in and six molecules of oxygen (O2) are released.

Oxygen production is directly tied to this photosynthetic process in plants. Factors like the plant’s size, age, health, and environmental conditions impact how much oxygen it can produce.

Estimated Oxygen Production of the Artillery Plant

While exact oxygen production can vary, it is estimated that a mature artillery plant can produce around 5-10 mL of oxygen per hour under optimal conditions.

To put this into perspective, here are some key facts:

-

5-10 mL is roughly equivalent to 0.2-0.4% of the oxygen required by one adult human per hour

-

A small 4 inch potted artillery plant produces enough oxygen to support one adult human for about 2-3 minutes per day,

-

10 medium sized artillery plants could produce enough oxygen to support one adult for 1 hour per day.

So while the artillery plant’s oxygen output may seem modest compared to large trees, collectively grouping many artillery plants together can notably enhance indoor air.

Impact on Indoor Air Quality

Indoor air quality has become an increasing health concern, especially with people spending more time indoors. Poor ventilation, chemical fumes, allergens, and pollutant accumulation can degrade indoor air.

Having indoor plants like the artillery plant can significantly improve air quality by:

-

Producing oxygen through photosynthesis.

-

Absorbing carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen.

-

Removing air pollutants like formaldehyde, benzene, and trichloroethylene through a process called phytoremediation.

-

Increasing humidity levels which can benefit respiratory health.

-

Reducing mold spores and allergens in the air.

Studies have shown that having indoor plants can reduce stress, increase productivity, and promote a healthier indoor environment through these air-purifying effects.

Tips for Growing Healthy Artillery Plants

To maximize oxygen production from your artillery plant, follow these simple care tips:

-

Light: Provide bright, indirect light avoiding direct sunlight.

-

Water: Keep soil consistently moist, water when top inch is dry.

-

Humidity: Maintain 40%-60% humidity, use a humidifier if needed.

-

Temperature: Ideal range is 65°F to 80°F.

-

Soil: Use a well-draining potting mix, repot annually.

-

Fertilizer: Apply a balanced liquid fertilizer every 2-4 weeks in the growing season.

With the right care, the artillery plant can thrive indoors while purifying the air. Group multiple artillery plants together to increase their collective oxygen output.

How Artillery Plants Compare to Other Houseplants

While the artillery plant produces notable amounts of oxygen for its size, other popular houseplants can output even higher amounts.

Here’s how artillery plant oxygen production compares:

-

Snake Plant: Produces up to 6-8 mL oxygen/hour, 1.5x more than artillery plant.

-

Peace Lily: Produces up to 7-9 mL oxygen/hour, almost 2x more than artillery plant.

-

Areca Palm: Produces up to 9-12 mL oxygen/hour, over 2x more than artillery plant.

-

Money Plant: Has an oxygen conversion rate of 6.5%, higher than the artillery plant.

So while the artillery plant contributes valuable amounts of oxygen, the snake plant, peace lily, areca palm and money plant are even better choices for maximizing air purification.

Interesting Facts about the Artillery Plant

Beyond oxygen production, here are some fascinating facts about this adaptable houseplant:

-

The artillery plant gets its name from its unique pollination method. The small flowers explosively eject pollen grains at up to 0.4 mph when disturbed.

-

Native to tropical and sub-tropical regions, it thrives in warm humid environments with average household conditions.

-

Features attractive bushy growth with delicate green leaves speckled in silver-white variegation. The variegated types require more light.

-

Extremely easy to care for, with flexible watering, light and fertilization needs. Can tolerate occasional droughts or forgetful plant parents!

-

Due to its resilient nature, it propagates readily from stem cuttings rooted in water or moist soil.

-

Displays most active growth and oxygen production in the spring and summer months. Growth slows in fall and winter.

-

Serves as a symbolic plant representing opportunity and prosperity in some cultures. Its resilience mirrors the human capacity to adapt and thrive.

Although a single artillery plant may only generate a modest amount of oxygen, collectively planting many artillery plants can notably enhance indoor air purification. Combined with other oxygen-producing plants, the artillery plant is an easy-care option to help create a healthier home environment.

With proper growing conditions and care, the durable artillery plant can produce oxygen while decorating any indoor space with beauty, visual interest and a touch of nature. Its lush leaves and unique resilience make it a staple houseplant with valuable air-purifying properties.

From a Nursery Start/Transplanting

When you buy a pilea, it may be very young or more mature. To transplant it to another container, or to pot up a stem cutting or division, do the following:

Choose a vessel that is large enough to accommodate the plant, whatever its size, with two to three inches of growing room all around it. Be sure that it has one or more drainage holes.

Keep in mind that when it’s mature, this type of pilea may be between 12 and 24 inches wide. You will probably need to repot more than once before maturity and may want to keep the early containers on the inexpensive side.

At maturity, you may opt to select a hanging container to showcase the species’ creeping, trailing nature.

Buy potting soil that’s rich in organic matter, moisture-retentive, loose and airy, and well-draining. It will approximate the 5.0 to 6.0 pH that this tropical species prefers.

Place a single layer of pea gravel in the bottom to facilitate drainage, and then fill the vessel about halfway with potting soil.

Gently unearth the plant from its current pot.

Settle it in the potting medium so it sits at the same depth it was in the original container.

Backfill with soil and tamp it very lightly to hold the plant upright. Take care not to compact the soil. Light and airy is what you want to aim for.

If you are potting a rooted stem cutting, settle it in the soil, taking care not to injure the fledgling roots.

Bury the rooted end one inch deep in soil, tamp lightly and loosely backfill.

To transplant a division, you’ll want to settle it in much the same way, with about an inch of soil over the roots, at about the same height it was in its original vessel.

After potting, water until it runs out the bottom of the vessel, and repeat.

When all drainage has stopped, find a location with bright, indirect light. You may want to place the container on a single layer of pea gravel in a shallow, non-rusting pan. Add water to the pan until it comes just to the top of the gravel.

This is a great way to increase ambient humidity and replicate the natural habitat of a pilea plant.

One final note: With stems that are fleshy like a succulent, it’s easy to bruise or break them, so be sure to handle yours with care.

Once potted and watered, it’s time to apply a half-strength liquid or slow-release granular houseplant food. It’s best to apply this to wet soil to avoid burning tender roots and stems.

Feed again in the summer, and continue to feed once in spring and once in summer going forward.

Some gardeners recommend feeding more frequently, but overfeeding may prove to be a disaster resulting in a visible buildup of salts on the soil and container that inhibits water uptake.

In the event of a buildup, flush the pot through several times with water, and reduce feeding to once a year in the spring.

Keep the soil evenly moist by watering when the surface feels dry. Avoid oversaturation, as the roots rot easily, and reduce watering during winter dormancy. Just don’t let the pot completely dry out.

In addition, avoid wetting the leaves, especially in low-light locations, to avoid creating a breeding ground for the bacterial and fungal diseases we’ll discuss shortly.

P. macrophylla is not hard to grow when you remember to:

- Use an organically-rich potting soil that is loose, well-draining, and moisture-retentive.

- Avoid packing the soil down hard when potting. Instead, tamp loosely and leave lots of air holes to facilitate the flow of nutrients, oxygen, and water.

- Fertilize sparingly to avoid a buildup of salts, and flush several times as needed in the event of overfeeding.

- Maintain even moisture without oversaturation by watering when the soil surface feels dry.

This is an easy species to maintain. For a more compact shape, pinch off a few inches of the growing tips. If you like, use them to make new plants per the propagation instructions above.

If a fragile stem breaks, use clean pruners to remove the damaged portion. Be sure to cut just above a leaf node to encourage rapid regeneration.

Also, tap water is sometimes so alkaline or “hard” that it causes white spots to form on the leaves. If you note this issue, switch to distilled water.

Like many houseplants of tropical origin, P. microphylla thrives in bright, indirect light but it can tolerate a low-light placement.

Photo by Daderot, Wikimedia Commons, via

P. microphylla ‘Variegata’ is a variegated pink and white cultivar you may like to choose for a location with bright indirect light.

P. microphylla ‘Variegata.’ Photo by Forest & Kim Starr, Wikimedia Commons, via

For best results in low light, remember that a green variety is your best bet, as a variegated one is likely to shade to dark green anyway.

This species has not been widely developed, and options and availability are currently not extensive.

Managing Pests and Disease

With indoor cultivation, you are not likely to face many issues. Some common houseplant pests prefer very dry environments, while fungi and bacteria favor dampness.

Try to keep the indoor humidity at or above 45 percent, and avoid both under- and overwatering as well as direct sunlight.

Even with the best care, pests may appear. You may encounter:

Some are more likely to prey upon flora grown outdoors, but you should be aware of the possibilities.

If a stream of running tap water doesn’t dislodge the offending insects, try one or more of the following:

Treat sapsuckers and caterpillars with an application of organic neem oil.

Apply food-grade diatomaceous earth to the soil. It addresses sapsuckers as well as flying pests and gastropods, and remains in the potting medium as a preventative measure against future infestation.

Place yellow sticky tape products formulated specifically for trapping flying pests near affected pots.

In the event of an extensive infestation, you may have to remove severely damaged foliage by cutting stems just above a leaf node or at the base.

As for diseases, the following are known to afflict P. microphylla:

- Anthracnose (Colletotrichum spp.)

- Myrothecium Leaf Spot (Myrothecium roridum)

- Pythium Root Rot (Pythium spp.)

- Rhizoctonia Aerial Blight (Rhizoctonia solani)

- Southern Blight (Sclerotium rolfsii)

- Xanthomonas Leaf Spot (Xanthomonas campestris)

As we said, indoor specimens are less likely to suffer from these ailments than plants grown outdoors.

However, if yours should become infected, there are both chemical and biological treatments for fungal and bacterial conditions that you can try.

If the damage is extensive, it is often better to discard the plant and sanitize the pot with a 10-percent bleach to water solution (one part bleach to nine parts water).

How many trees does it take to produce oxygen for one person?

FAQ

How much oxygen is produced by one plant?

How much oxygen does a spider plant produce per day?

How much oxygen does one house plant produce?

How often should I water an artillery fern?

What is an artillery plant?

Artillery plants can also provide fine succulent-textured, green foliage for containers as the flowers are not showy. Related to the aluminum plant and the friendship plant of the genus Pilea, artillery plant info indicates this plant got its name from its dispersal of pollen.

How many oxygen-producing plants do I Need?

However, some gardeners recommend that you need at least two big leafy oxygen-producing plants for every 100 square feet (or 9.3 meters) of space in your house. Adding oxygen-producing plants to your home only offers benefits if you suffer from breathing and lung diseases.

Where do artillery plants grow?

The artillery species is native to the Caribbean, Mexico, Central and South America, and the southeastern United States. In its native habitat, it is a somewhat weedy, spreading ground cover that commonly sprouts between rocks and in lawns, in margins between land and water, and in masonry crevices.

What does an artillery plant look like?

The artillery species has plump leaves like a succulent. They are either green or variegated pink and white, one-eighth to one-half inch long, and “obovate,” or rounded and narrower at the base. The leaves are arranged in opposing pairs, like a fern frond. In nature, the species produces tiny pinkish flowers followed by brown fruits.